To close the gap between UK society’s expectations and public sector capacity we need to think differently, says Duncan Shaw and Andrew McClelland.

Covid-19 shone a light on many aspects of our society, good and bad. Five years on from the pandemic, it is crucial to focus on prioritising our resilience to disruption as we assess where the greatest risks lie today and in the future.

These risks can be physical, for instance the resilience of our infrastructure to major weather events, and societal, namely ensuring that those who are most vulnerable in our society can be properly cared for.

In terms of the former, the recent shutdown of Heathrow was just the latest example of how prepared we need to be in case of disruptive events (in this case an electricity substation fire near the airport) impacting the UK’s critical infrastructure. The incident demonstrated the inherent complexity and interconnectedness of our infrastructure systems, a point often overlooked by the news media. The Government has since announced an inquiry into what precisely happened at the UK’s busiest airport.

Societal risks

In terms of societal risks the picture can be equally as challenging, especially against the backdrop of a rising and rapidly ageing UK population, the fallout from geopolitical instability, and both central and local government finances under huge stress.

For instance, headroom in both the NHS and across our emergency services is incredibly small right now. The NHS has very little ‘surge capacity’ to cope with a major national health incident, while our emergency services are under stretch like never before in terms of reaching incidents quickly enough.

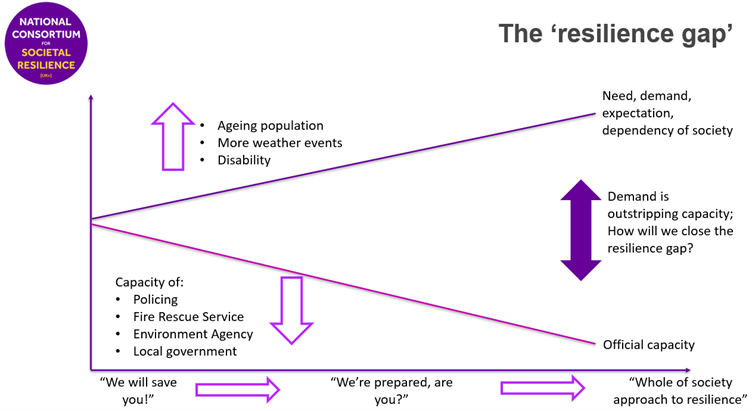

Ten or 20 years ago the narrative would have been that the emergency services would always be there for you, whatever your problem or situation. Today this is simply no longer the case. There is a growing and rising gap between our expectations of emergency response and its capacity because a) demand is rising so quickly, and b) resources are so finely stretched.

We cannot tell you here exactly why demand is increasing so, but what we do know is that resources are most definitely under pressure and we see this every hour of every day with longer and longer wait times. Incidentally this isn’t a problem just here in the UK. It doesn’t matter which country we are in, but when we show the ‘resilience gap’ chart below to groups of academics or political and business leaders, everyone nods.

Helping the vulnerable

It goes without saying that we want to avoid harm and suffering, and as a society do all we can to help vulnerable people and reach out to them. In the UK, let’s assume that around four fifths of people are pretty resilient and can take decisions that protect themselves in a disruption. For the remaining 20% daily life can be a constant challenge. But instead of the majority of us thinking that the care of the 20% is someone else’s problem, its everyone’s challenge – the 80% can think about how they can help the 20% more.

Some lessons from Covid are worth remembering here. The knock on the neighbour’s door to check they are ok. Identifying who in your street may be in need. Using social media networks to organise local communities effectively. It comes down to identifying the 20% at risk and understanding their vulnerability. The 20% may think very differently about life and may not have the agency, the financial resources, or the same levels of resilience as the 80%.

Five years on

Five years on the UK is beginning to learn the lessons from Covid-19. For instance, in the wake of the first stage of the Covid inquiry the previous government changed the structure of the National Security Risk Assessment (NSRA) by introducing a more dynamic assessment process that allowed risks to be regularly re-assessed, drawing on new and critical information. The NSRA moved to a dynamic risk assessment process that enables risks to be refreshed more regularly, allowing the Government to track changes to the risk landscape over time. We see momentum continuing to build around this important area across all Government departments.

Here at Alliance Manchester Business School we have also made strides in responding to these challenges and being at the forefront of debate and research. Specifically, we have founded the National Consortium for Societal Resilience [UK+] to enhance the UK’s whole of society approach to resilience so that individuals, community groups, businesses, and organisations can all play a meaningful part in building the resilience of our society. Indeed, last month the Consortium welcomed over 160 people for its third annual conference at The University of Manchester, a vindication if it were needed of the critical importance of this issue.

Duncan Shaw is a co-investigator on the RBOC project and Professor of Risk, Resilience, and Society at Alliance Manchester Business School. Duncan is also a SALIENT work package lead for Behavioural and Cultural Resilience

Andrew McClelland is a researcher on the RBOC project.