By SALIENT co-investigator Michael A. Lewis, Professor of Operations and Supply Management, University of Bristol

I have finally read Priya Satia’s prize-winning history, Empire of Guns, which firmly connects Britain’s industrial revolution to the state’s demand for weapons. Showing how the military as much as markets drove industrial experimentation. It also includes a fascinating nineteenth-century manufacturing story with contemporary industrial strategy resonance.

Samuel Colt patented the revolving-cylinder pistol in 1836 and went on to become one of the wealthiest men in America through his revolutionary firearm designs and pioneering mass production techniques. The original ‘defence bro,’ he then set out to establish a factory in Europe and chose London. At the time, Britain was urgently and somewhat chaotically preparing for war in Crimea against Russia.

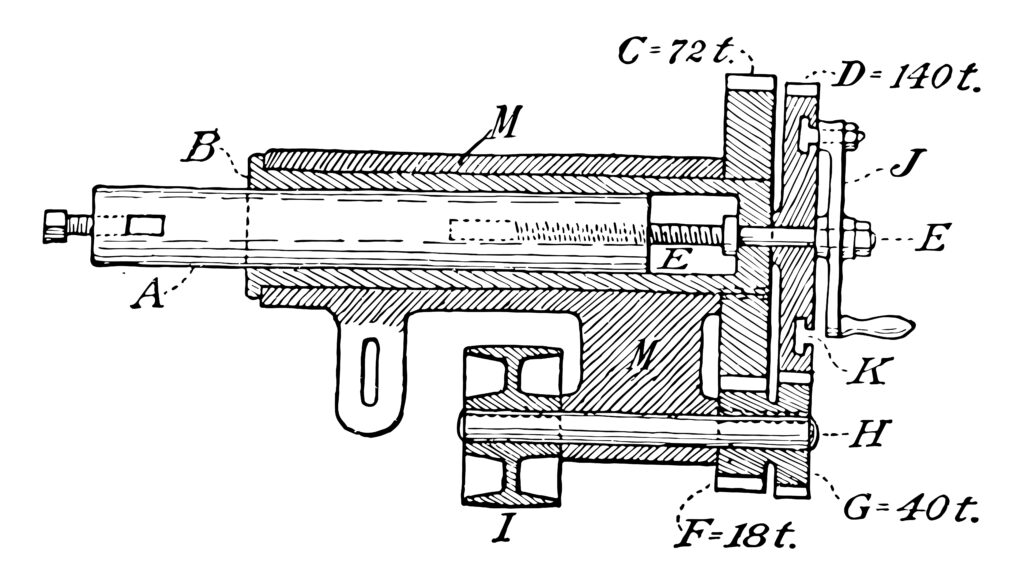

He arrived in 1853 with a system of gauged manufacture and interchangeable parts that few British makers had mastered. Over three hundred machines shipped from Hartford were installed in his Pimlico facility, supported by skilled US machinists to train the British workforce. Household Words, the weekly magazine edited by Charles Dickens, published a report by William Moy Thomas on a visit to Colt’s factory in May 1854:

“This little pistol which is just put into my hand will pick into more than two hundred parts, every one of which parts is made by a machine. A little skill is required in polishing the wood, in making cases, and in guiding the machines; but mere strength of muscle, which is so valuable in new societies, would find no market here — for the steam engine — indefatigably toiling in the hot, suffocating smell of rank oil, down in the little stone chamber below — performs nine-tenths of all the work that is done here.”

Moy Thomas also highlighted what made Colt’s production methods distinctive:

“The bores of barrels and cylinders must be mathematically straight, and every one of the many parts must be exactly a duplicate of another. No one part belongs, as a matter of course, to any other part of one pistol; but each piece may be taken at random from a heap, and fixed to and with the other pieces until a complete weapon is formed; that weapon being individualised by a number stamped upon many of its component parts.”

Colt aimed to scale revolver production rapidly, supplying both the War Office and the Admiralty, and achieved significant technical success: London Proof House records show 13,916 revolvers tested in 1853. Yet by 1856, the factory had closed.

Strategic Procurement and Capability Transfer

The Colt manufactory reflects how Britain managed defence capability during this period of institutional strain. Procurement was deliberately fragmented: Colt secured sizeable Admiralty contracts — around 4,000 revolvers in 1854 — and smaller Army orders, but these were released in batches and never converted into long-term volume commitments. Colt lobbied aggressively for exclusive contracts but failed.

The broader context was one of institutional weakness and crisis-driven improvisation. The Crimean War had exposed serious failures in planning and supply. In January 1855, Parliament condemned ministers for entering the conflict “in the most utter ignorance of the power and resources of the enemy… [and] the supplies which your army would need.” Small-arms shortages forced emergency imports of rifles and revolvers from the USA, Austria, and Belgium. Later, bureaucracy also shaped Colt’s fate: in 1855, the Board of Ordnance — the body responsible for weapons procurement — was abolished, with responsibilities transferred to the War Office. Procurement fragmentation reflected both deliberate policy and institutional fragility: the War Office spread contracts across suppliers to avoid dependency, but the collapse of the Board and the urgent demands of war layered improvisation on top of strategy. Pimlico succeeded technically but operated in an unstable environment where strategic control and crisis-driven decision-making collided, and the manufactory could not survive that tension.

Yet within this apparent chaos lay a more systematic approach to technology acquisition. Colt was part of a much broader tooling revolution. Robbins & Lawrence of Windsor, Vermont, had pioneered high-precision milling machines and gauges for interchangeable rifle manufacture. British officials had seen their tooling at the Great Exhibition in 1851 and ordered 152 rifle-making machines, which were later installed at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield. Colt’s Hartford armoury drew heavily on these same designs, meaning Pimlico operated within this shared ecosystem of American advanced precision manufacturing.

When the manufactory closed in 1856, much of the facility was absorbed into Enfield, which by the late 1850s was producing over 100,000 rifles annually. This capability transfer succeeded precisely because the technologies were decomposable. Colt’s gauges, fixtures, and milling machines could be bought, studied, and replicated. Skilled machinists absorbed tolerances and carried them into UK facilities. Once the machinery was installed and methods embedded at Enfield, Britain controlled the capability without Colt. Pimlico closed, but the production logic endured.

Contemporary Parallels, Structural Differences

It’s not a straight line from Samuel Colt to Palmer Luckey of course, but there are modern ‘rhymes’ worth noticing. UK Defence Industrial Strategy (2025) explicitly seeks to rebuild sovereign capacity, promising new munitions plants, long-range weapons pipelines, and expanded autonomy programmes. The strategic logic echoes the 1850s: harness foreign expertise while building domestic capability, maximise value from international partnerships, and achieve greater strategic independence.

And overseas defence firms are again opening UK factories — most notably Anduril’s planned facility to produce its Roadrunner drones and counter-UAS systems. On the surface, this appears like Colt’s manufactory again: a wealthy, high-profile entrant bringing disruptive advanced manufacturing to meet urgent MOD demand, operating within a broader push to rebuild defence capacity.

But there are fundamental differences. The technologies Britain now seeks — AI-enabled targeting, autonomous decision engines, software-defined swarms — are not decomposable in the way Colt’s manufacturing methods were. Where Colt’s gauges and milling machines could be purchased, mastered, and replicated, Anduril’s drones are inseparable from its proprietary autonomy stack. The algorithms that enable target recognition, flight control, and swarm coordination represent years of machine learning development, continuously updated through software architectures deliberately designed to resist extraction or replication. Reproducing these capabilities would require access to vast proprietary datasets collected across thousands of operational hours, continuous telemetry pipelines that feed updates back into the models, and the private infrastructure needed to maintain and deploy them. Even with the source code, the absence of these data and integration rights makes replication effectively impossible.

If Britain wants to rebuild industrial capacity without locking itself into new forms of dependency, the answer is probably not trying to prise open proprietary code. The UK’s experience as the sole Tier 1 partner on F-35 is instructive here: despite committing over £2bn and securing substantial production workshare, it never gained access to the core mission systems. This left Britain dependent on US-controlled software pipelines for upgrades and integration, underscoring that industrial participation does not automatically translate into sovereign capability when software-defined systems are involved.

That experience illustrates why modern capability cannot simply be bought: when the value resides in proprietary software, control over the hardware is not enough. The more practical route is to shape agreements, so Britain controls the layers that matter most: data, interfaces, and the ability to integrate its own systems. In practice, that means trying to structure contracts to guarantee ownership of mission data generated by UK-deployed systems, ensuring open integration rights so British platforms can connect to wider defence networks on UK terms, and securing the ability to re-host or replace autonomy services if a supplier withdraws. These principles seem to be shaping programmes like the Global Combat Air Programme, where the UK, Japan, and Italy are designing modular architectures specifically to avoid single-vendor lock-in. Applied to Anduril and similar entrants, this presumably means we are also securing clear rights over mission data, interoperability, and system portability from the outset?

Building factories alone will not restore sovereignty unless Britain also secures control over the software, the data, and the networks that now define capability.

This article is republished from MADE GROUND.