By Richard Kirkham, SALIENT Academic Lead

I was delighted to be invited by SALIENT colleague Prof. Mark Elliot and the SPRITE+ plus team to speak at an online ‘Sandpit’ event on the 3rd of June 2025 – where we explored issues associated with resilience and TIPS (Trust, Identity, Privacy and Security). The session was a pre-cursor to an ‘in-person’ event, due to take place in mid-June, where we hope to support researchers in developing high-quality proposals for the upcoming round of SPRITE+ funding. In the longer-term, our ambition is to support SPRITE+ projects that demonstrate exceptional promise, with additional funding from SALIENT – the idea being to resolve the problems often associated with ‘short-term’ investments such as post-doctoral researcher recruitment and retention.

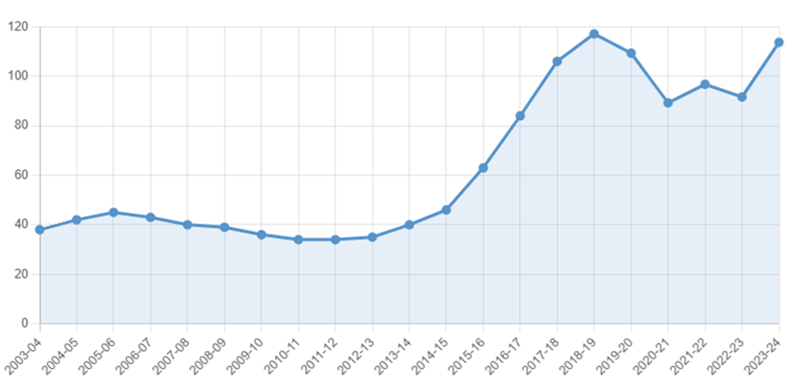

In the sandpit, I sought to challenge some of the solutions that are being proposed (mainly by politicians) in response to increasing levels of violence in UK prisons. Recent incidents at HMPs Frankland, Long Lartin and Belmarsh (all high security prisons) illustrate the dangers faced by prison officers in what is largely an undervalued part of the UK civil service. During the period 2013-2019, there was a rapid increase in the number of assaults against staff, mirrored by an almost identical ‘prisoner-on prisoner assault’ trend during the same period.

Fig 1: Assaults on staff per 1,000 prisoners (Ministry of Justice, 2025)

The explanatory factors are multifaceted, but at the root is chronic underinvestment in the prison service. In 2020, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) enquiry into ‘Improving the Prison Estate’ concluded that

‘The Prison Service has been operating hand to mouth, by reacting to immediate crises rather than developing a long-term strategy for the prison estate.’

As an ‘unprotected’ department, the impacts of decisions taken during the 2015 spending review began to crystallise.

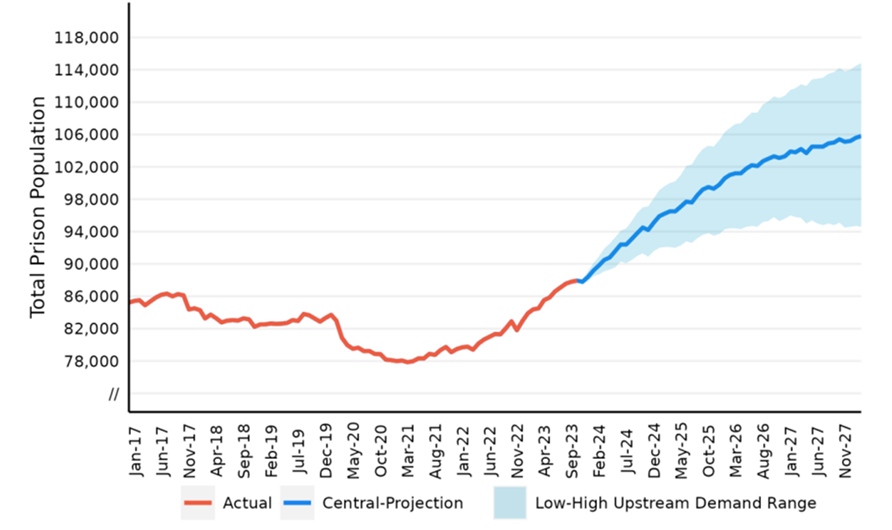

Fast-forward to autumn 2024, and with a new government in place, the prison ‘crisis’ began to dominate the media headlines once again. The prison population was increasing, whilst capacity was unable to keep pace. Then came Southport, and the civil disobedience and rioting that took place in the aftermath. This led to further unexpected demands on the courts and ultimately, the prison service.

Fig 2: Total prison population projection, December 2023 to March 2028 (Ministry of Justice, 2025)

In November 2024, the new administration published a policy paper entitled ‘10-year Prison Capacity Strategy: A strategy to deliver 14,000 prison places and create a resilient prison estate.’ This followed an earlier decision to vary the automatic release dates for some prisoners so that they leave custody after serving 40% of their sentence, rather than 50%. – the scheme was known as SDS40 and proved to be very controversial. The government argued that it was left with little other option due to a lack of resilience in the prison estate.

In parallel, the prison service is facing a ‘crisis;’ in a recent report by the Institute for Government, they portray a‘…prison system in England and Wales [that] is in an extremely poor state. Levels of violence, self-harm and drug use are shockingly high, prisoners’ work and education opportunities severely limited. Buildings are crumbling or in severe disrepair, many dangerously so, and physical conditions often unsanitary. Inexperienced staff are struggling to cope with these increasingly fraught circumstances.’ What to do?

Data and evidence

The problems are known, and have been for some time. The Ministry of Justice’s time series forecasts [Fig 2] evidence the immediate need for improvements to capacity and resilience of the prison service. Aside from the annual reports of Independent Monitoring Boards and the work of the Prison Reform Trust, there are numerous other statutory and non-statutory bodies that have evidenced the ‘crisis’ in the prison service – this includes HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, the Care Quality Commission and OFSTED. One may argue that we have too much data and Minister’s struggle to grasp the core messages.

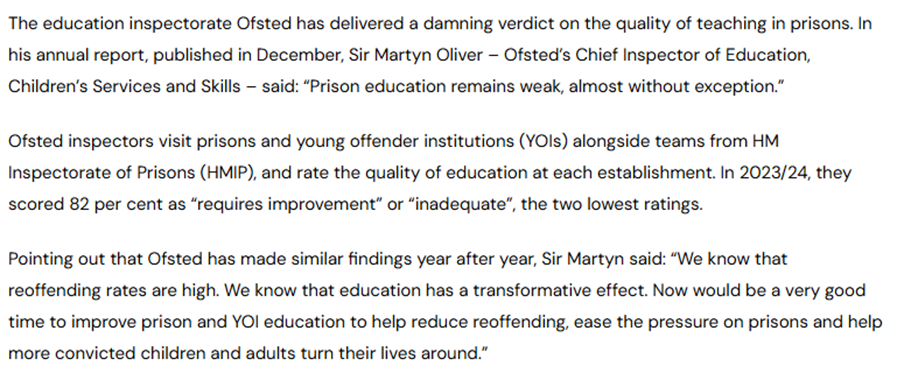

In a recent edition of the prisoner’s newspaper ‘Inside Times;’ an article on OFSTED’s annual report elegantly illustrates how, despite evidence of the benefits of good education in prisons, the quality of provision remains weak.

Solutions, and re-imagining solutions

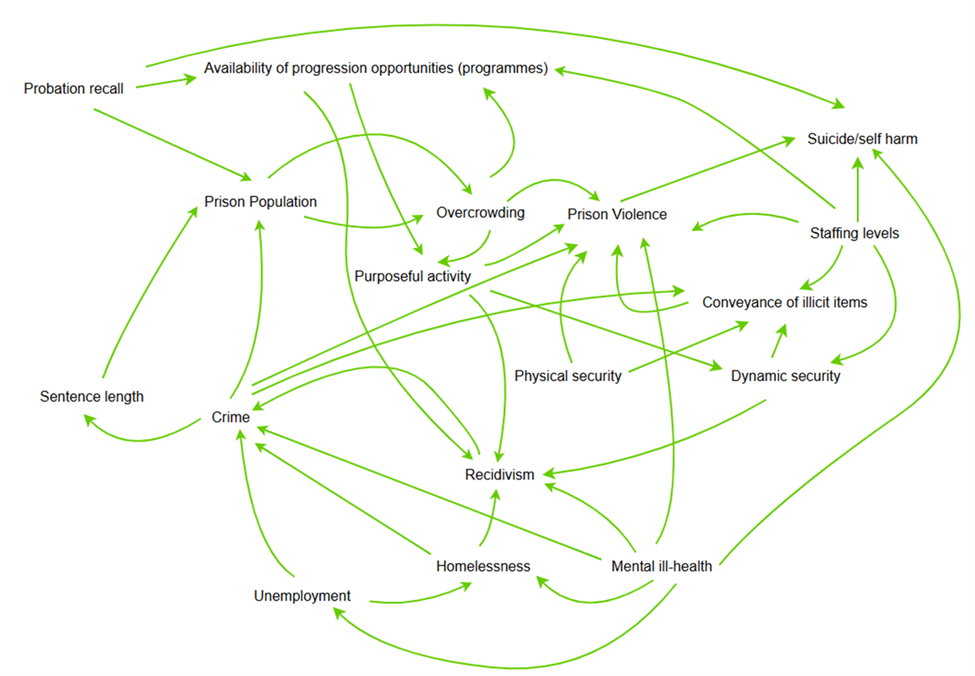

Complex and deep-seated challenges of the type being endured in our prisons are unlikely to be resolved through simplistic interventions. I am deeply sceptical of the idea of equipping prisoner officers with ‘tasers, stun grenades and baton rounds’ as a response to the issues of violence in prisons. Nor do I think that ‘supermax’ style prisons are compatible with a country that has signed and ratified the UN Optional Protocol (OPCAT). If we look beyond the rhetoric and political soundbites and adopt a system view, it is possible to recognise that the antecedents to custody are issues largely outside the control of the prison service. And herein lies the paradox; it is the duty of the prison service to help prisoners lead ‘law abiding and useful lives in custody and after release’ – yet in actuality, it has very little influence on the latter. For example, homelessness is one of the main factors in recidivism – and as one former prisoner said to me… ‘my life is an endless cycle of cell-street-repeat’

Prior to the sandpit, I sketched out a ‘rough and ready’ casual model based on the evidence that I know of, and my own (20+ years!) experience of prisons. The antecedents to prison violence include overcrowding, lack of purposeful activity, staffing levels, security, and mental-ill health. We know this from the subsequent report into the ‘Strangeways Riots’ in Manchester in 1990. As a curious aside, the riots were entirely predictable based on the narratives presented in two documentaries by the BBC (1952) and the iconic Granada TV ‘World in Action’ team in 1979.

It is absolutely right that the prison service implements immediate measures to protect staff from the harms of prison violence, indeed the same must be said for prisoners in the custody of the service. However, the systems perspective suggests that solutions to reducing prison violence and increasing the resilience of the prison service lie in strategies that are designed to reduce the prison population. This requires a ‘whole of government approach’ involving departments across Whitehall; homelessness (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government), unemployment (Department for Work and Pensions) mental ill-health (Department of Health and Social Care) and crime (Home Office). This brings into play the question of the role of the ‘machinery of government’ – is it currently fit for purpose, or do we need radical transformation in the ways and means of spending reviews and how these dictate economic and political decision-making.

Conclusions

- Simplistic interventions to complex problems are unlikely to offer sustainable solutions to intractable issues.

- Technology centric solutions in isolation of a human-centred approach are unlikely to tackle the root causes of complex problems.

- A system thinking approach can illustrate how the problems in (say, prisons) are often a reflection of wider (societal) problems.

- A ‘human-centred‘ approach to problematisation may be useful in pointing us towards effective solutions.

References

- Inside England and Wales’s prisons crisis: Summary, Institute for Government, March 2025